April is Sjögren’s syndrome awareness month. Since Sjögren’s (pronounced SHOWgrins) is the second most common cause of autonomic neuropathy, Dysautonomia International will be posting Sjögren’s/dysautonomia related info this month on social media, starting with this blog post.

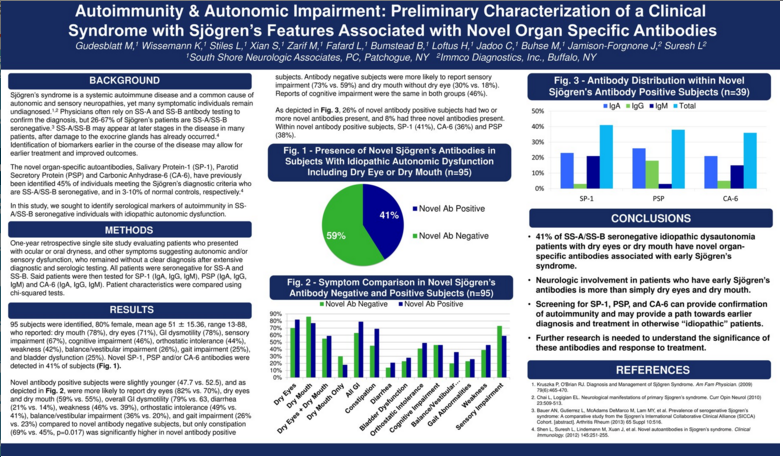

Dysautonomia International President Lauren Stiles was diagnosed with POTS and Sjögren’s syndrome in her early 30s, younger than the typical Sjögren’s patient. She co-authored a research study on Sjögren’s syndrome related antibodies in dysautonomia patients that was presented at the 2016 American Academy of Neurology annual meeting. The study found that 41% of idiopathic dysautonomia patients who reported either dry eyes or dry mouth had antibodies that are found in the early stages of Sjögren’s syndrome.

Dysautonomia Dispatch Blog Editor Emily Deaton interviewed Lauren to answer some of the questions we received after we shared the initial abstract.

Autoimmunity & Autonomic Impairment: Preliminary Characterization of a Clinical Syndrome with Sjögren’s Features Associated with Novel Organ Specific Antibodies.

Autoimmunity & Autonomic Impairment: Preliminary Characterization of a Clinical Syndrome with Sjögren’s Features Associated with Novel Organ Specific Antibodies.

Q: Can you explain this study in plain English?

A: Sure. Dysautonomia International collaborated with the neurologists at South Shore Neurologic Associates in New York and Sjögren’s researchers at SUNY Buffalo. We looked at the records of all of South Shore Neurologic Associates’ patients over the past year who reported either dry eye or dry mouth symptoms, plus some kind of other autonomic problem, who didn’t have an identifiable cause (meaning their dysautonomia was “idiopathic”), and who didn’t have the SS-A and SS-B antibodies doctors common rely upon to diagnose Sjögren’s. Out of 95 idiopathic dysautonomia patients included the study, we found that 41% of them had one or more novel early Sjögren’s antibodies (salivary protein-1 [SP-1], parotid secretory protein [PSP], and/or carbonic anhydrase-6 [CA-6]). Then we looked at the symptoms found in the antibody positive patents compared to the symptoms in the antibody negative patients. They essentially had the same symptom profiles, but the antibody positive patients were more likely to have constipation.

Q: What type of dysautonomia did the patients in this study have?

A: Rather than focusing on the formal diagnostic criteria used to classify the different types of dysautonomia, we focused on the symptom presentation. We looked at symptoms suggesting autonomic dysfunction: orthostatic intolerance, bladder dysfunction, secretory dysfunction (dry eyes/dry mouth), and gastrointestinal dysfunction. The study included individuals who had previously been diagnosed with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, neurocardiogenic syncope, orthostatic hypotension, orthostatic intolerance, and gastroparesis, which are all forms of dysautonomia. Sjögren’s is the second most common cause of autonomic neuropathy, after diabetes, so it’s not surprising that we would see a wide variety of dysautonomia patients who have markers associated with Sjögren’s syndrome.

Some of the study subjects had also been diagnosed with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, mast cell activation syndrome, chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, Lyme disease, and other overlapping conditions seen in our patient community.

Q: Do these antibodies cause dysautonomia?

A: The antibodies involved in this study (SP-1, PSP and/or CA-6) are targeting the salivary glands, so they may be causing or contributing to dry mouth, but we don’t think they are causing all of the other aspects of dysautonomia in these patients. These antibodies have been identified early in the course of Sjögren’s syndrome in two mouse models of Sjögren’s and in humans. Sjögren’s comes with a lot of different antibodies, so there are likely other antibodies or immune markers in these patients that are disrupting the autonomic nerves, resulting in dysautonomia symptoms.

One likely culprit is muscarinic-3 receptor antibodies, which have been found in up to 90% of Sjögren’s patients in other studies, particularly Sjögren’s patients who are younger or earlier in the course of the disease. Muscarinic-3 (M3) receptors are part of the autonomic nervous system. When an M3 antibody binds to these receptors, this can impair the messages sent between the autonomic nerves, resulting in symptoms of dysautonomia. Unfortunately, reliable M3 antibody testing is not commercially available at this time. However, we are working on a study with Dr. Steven Vernino at UT Southwestern to look for these antibodies in POTS patients.

A: If you have any symptoms of dry eyes or dry mouth, you can ask your doctor to test you for the early Sjögren’s antibodies. Your doctors may not have heard about these antibodies, but you can show them this website about the panel. The panel includes the early Sjögren’s antibodies (SP-1, CA-6 and PSP), with an option to include commonly tested Sjögren’s antibodies (SS-A, SS-B, ANA, RF). Your insurance company may cover the test. Most doctors will not diagnose Sjögren’s based on the early Sjögren’s antibodies alone, but they may be helpful in making a diagnosis in patients who present with symptoms of Sjögren’s (dryness, neuropathy, dysautonomia, fatigue, joint pain, etc.) in light of other Sjögren’s tests results too.

Q: Is Sjögren’s common in dysautonomia patients?

A: Sjögren’s is the second most common cause of autonomic neuropathy, after diabetes, and has been associated with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, orthostatic hypotension, orthostatic intolerance, autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy, gastroparesis, and other forms of dysautonomia. In fact, the dry eye that Sjögren’s is well known for is a symptom of dysautonomia, since the tear glands are controlled by the autonomic nervous system. 1 in 10 people who have dry eye have Sjögren’s syndrome. Sjögren’s impacts 4 million Americans, but 3 million of them are undiagnosed.

Q: Isn’t Sjögren’s an older woman’s disease?

A: The stereotypical Sjögren’s patients is a Caucasian woman over age 40. However, Sjögren’s can occur in any race or ethnicity, and 10% of patients are male. While Sjögren’s is not as common in children as it is in adults, it can occur at any age. The youngest novel Sjögren’s antibody positive patient in our study was 13. Younger Sjögren’s patients tend to present with different symptoms than older patients, with more neurological symptoms and less dryness. The dryness usually develops slowly over time as the disease progresses.

The current diagnostic criteria for Sjögren’s were developed based on studies of older patients who have advanced/severe dryness associated with their Sjögren’s. Many experts now agree that the current diagnostic criteria are not catching patients who are at an earlier stage of the disease, who tend to be younger and have less severe dryness, when you may actually be able to prevent some of the long term damage from occurring. People diagnosed with Sjögren’s in their 50s have probably been dealing with it for 20-30 years before they were “sick enough” to get diagnosed.

Q: Can you grow out of Sjögren’s?

A: Unfortunately, no. There are a small percentage of patients who may go into remission, but for most patients Sjögren’s is a slowly progressive, systemic autoimmune disease. Diagnosing and treating it as early as possible can help slow down the progression and can help avoid serious organ and neurological complications.

Q: Can Sjögren’s cause problems other than dysautonomia?

A: Definitely. Sjögren’s is one of those diseases where everyone can present with different symptoms. Fatigue, muscle pain, and joint pain are very common amongst Sjögren’s patients. Some patients have a limited disease that primarily impacts their exocrine glands (tear, salivary, and other moisture producing glands throughout the body). But most patients develop one or more extra-glandular complications, such as vasculitis, interstitial lung disease, renal tubular acidosis, atrophic gastritis, liver disease, gall bladder disease, pancreatitis, or neuropathy. Sjögren’s can attack any part of the nervous system, from the brain to the small fiber nerves in your skin. About 50% of Sjögren’s patients have a second autoimmune disease, most commonly rheumatoid arthritis, lupus or Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

A: Arrgh, no! A lot of doctors don’t really know anything about Sjögren’s (just like dysautonomia), so they may assume it’s just a “dry eyes and dry mouth” problem that can be easily treated with eye drops and mouthwash. This is completely false. Sjögren’s is a progressive, systemic autoimmune disease. It’s essential to get diagnosed and treated as soon as possible to prevent long-term complications. Sjögren’s comes with a 44-fold increased risk of lymphoma, doubled risk of heart attacks, increased risk of stroke, increased risk of fetal heart block, dental decay, corneal damage, organ damage, and a really terrible quality-of-life if left untreated. You deserve to know if you have it or not, so that you can obtain proper medical care. Your family also deserves to know, because autoimmune diseases often run in families. If you have dry eyes or dry mouth that is not due to medication (many medications cause dry mouth), plus dysautonomia symptoms, and your doctor won’t help you get tested you for Sjögren’s, find a better doctor. Many of the autonomic neurologists listed on Dysautonomia International’s physician listing know how to screen a patient for Sjögren’s. Another way to find a good Sjögren’s doctor is by contacting the closest chapter of the Sjögren’s Syndrome Foundation, and asking them who the best doctors are to diagnose Sjögren’s in your area. Keep in mind that most Sjögren’s doctors are rheumatologists, and they generally don’t deal with the neurological aspects of Sjögren’s, like dysautonomia.

Q: What are the treatments if I have Sjögren’s?

A: While there is no cure for Sjögren’s, there are many treatments available to minimize symptoms and reduce the risk of complications. Pharmacological treatments include lubricating, autologous serum, or cyclosporine eye drops, punctal plugs, lubricating mouth washes, mouth rinses to help remineralize teeth, pilocarpine, cevimeline, hydroxychloroquine, and in more severe cases, immune modulating treatments like high dose steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, mycophenolate, or rituximab. There are several new immune modulating treatments being explored. Treatment is very individualized and most pharmacological treatments are not FDA approved specifically for Sjögren’s. Lifestyle measures, like using humidifiers, consuming an anti-inflammatory diet, regular exercise, stress management, and proper sleep, also play an important role in the management of Sjögren’s.

Q: Why do you talk about Sjögren’s so much?

A: Good question! I do talk about it a lot because that’s the root cause of my dysautonomia and alphabet soup of other diagnoses, and I want to make sure patients are getting properly screened for it. Sjögren’s is a common cause of dysautonomia, but it’s treatable in a way that is completely different than how we treat most other causes of dysautonomia. And if you have Sjögren’s, but remain undiagnosed and untreated, your chances of getting better are slim. Sjögren’s rarely improves on its own. It’s slowly progressive, so it’s critical to be diagnosed as soon as possible if you have it. Given the known overlap between Sjögren’s and dysautonomia, I suspect there are many undiagnosed Sjögren’s patients within the dysautonomia community. This study confirms that suspicion – 41% of idiopathic dysautonomia patients with dryness is a lot of people! Just like dysautonomia patients, Sjögren’s patients experience significant diagnostic delays due to a lack of public and physician awareness. The Sjögren’s Syndrome Foundation has set a goal of reducing the average diagnostic delay in Sjögren’s from 4.7 years to 2 years in the next five years. Anything I can do to help dysautonomia patients who may have undiagnosed Sjögren’s “find their root cause,” I’m happy to help.

I am very interested in other causes of dysautonomia too, because we need to understand all of the root causes to be effective advocates for our patient community. One of the things we’ve been able to do with Dysautonomia International is identify patients who have expertise in their own diagnoses (EDS, MCAS, Lyme, Chiari, Sjögren’s, lupus, celiac, antiphospholipid syndrome, CRPS, gastroparesis, etc.) and engage them in research and physician education – because we need the researchers and physicians to understand all of these things and figure out how they are related, or not related. We won’t be satisfied until we’ve found everyone’s root cause, more effective treatments, and a cure for all of us.